Episode 11: Boomers who Rock

In this episode:Thinking of rocking into your retirement? Want to know more about your aging rockstar idols?

Featuring Stephen Katz (Professor Emeritus, Sociology, Trent University) talking with host Sally Chivers about:

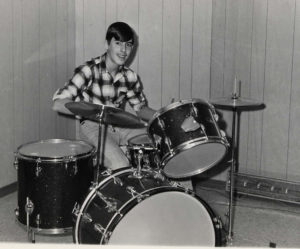

- How he learned to play the drums

- Wanting to be a Beatle

- Why boomers still rock

- Rockstar fantasies

- The boys in the band

- The mature imagination

Watch The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan show.

Find Norma Coates’s article Mom Rock? Media Representations of “Mothers Who Rock”

Watch Stephen Katz rockin’ with the Neckties

And with his previous band Essential Soul:

Wrinkle Radio is a proud member of the Amplify Podcast Network. We are grateful for funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada and support from Aging in Data and VoicEd Radio.

Stephen Katz [00:00:03]:

So these four guys from Liverpool, playing to thousands of screaming fans with such sexual and fashionable and musical freedom, became this boomer blueprint, became this other way to be. Almost every current boomer rocker will tell you that watching the Beatles on Ed Sullivan did something for them as a founding moment, that something changed for them. Even the unfamous boomer feels that music and identity are braided together kind of since that time. That, yes, you can keep your day job and worry about your mortgages and have families, but you are also this other thing always in the back of your mind, too, this Beatle possibility.

Sally Chivers [00:00:56]:

Welcome to Wrinkle radio, where the stories we tell about aging matter. I'm your host, Sally Chivers, and I am so glad you're here. I'm joined again this episode by Stephen Katz, and we're going to talk about boomers who rock. Boomers like Stephen. At the end of last episode, I left you wanting to hear more of the story about how Stephen changed from a boomer kid into a boomer kid who rocked the drums.

Stephen Katz [00:01:32]:

I had started playing on overturned pails originally, before I had drums in the basement. They called it thumping upstairs. Neil Peart said the same thing. He had overturned pails of some kind, plastic buckets. Almost every boomer who didn't get drums yet played something like that. Pails, buckets, pots and pans, wrecking whatever kitchen items or basement items in the process. I didn't have any drumsticks, so I noticed in my art class that if you took paintbrushes and turned them around, they made pretty good drumsticks, you could hit stuff with them and bang around stuff. So I was banging around an art class, pulled the brush ends off, and went home and played my tubs, put on the little record player, put on the Beatles record, or.

Stephen Katz [00:02:23]:

By then we had other groups, the Dave Clark Five and the Rolling Stones and the Animals, buying all these singles and thumping away downstairs on these tubs with yelling upstairs, will you shut up down there, you know kind of, what the heck are you doing? This became my first kit and where I really practiced and practiced and practiced. I had those paintbrushes for ages, even after I got drums and real drumsticks and everything. They were so sentimental to me and so important to me.

Sally Chivers [00:03:03]:

That's Stephen Katz, professor emeritus of sociology at Trent University. I knew Stephen was a drummer. I've always wanted to see him play. I never pictured him drumming as a little kid. This really made me think of the little kid in Love, Actually. This little kid is distraught, and his stepfather is beside himself trying to figure out what must be wrong with this kid whose mother has just died. And it turns out that to the child, the problem is much bigger. It is impossible.

Sally Chivers [00:03:42]:

He is in love, and he cannot even get this girl at school to look at him. And then the kid has an idea: he'll become a musician because girls love musicians. And so he gleefully takes up the drums. And then there's a humorous montage sequence of him practicing day and night. His stepfather is pacing the hallway in his pajamas, covering his ears. There's these teenagery notes showing up on the little kid's door, saying things like, keep out. And I told you I'm not hungry. It's one thing to become a rock musician, but it's a special kind of torture to your loved ones to become a drummer.

Sally Chivers [00:04:34]:

So I asked Stephen not just about his interest in rock music, but specifically in why he wanted to be a drummer. Was he just trying to piss his parents off?

Stephen Katz [00:04:45]:

Well, yes, but that wasn't really it. Two things kind of happened one day in class in 1963, I guess in the fall. I was eleven years old, sitting in my grade six class, and one of my classmates, a young girl named Wendy, turned around with this black and white beaten up picture of four guys who had the weirdest hair I've ever seen, and suits without collars, and just looked incredibly strange. And at first I thought they were clowns. I said, wow, those are a group of clowns. I wonder. They must be funny, you know? And Wendy said, no, they're the Beatles, and we all love them.

Stephen Katz [00:05:27]:

All the girls here, we love the Beatles. And I said, let me see that picture. And we're kind of. No, no, you're going to tear it. It's like sacred. It's a relic. And I thought, the Beatles. Who are these people? And then I look around at the boys in my class, brush cuts, plaid shirts done up to the top button, cold weather corduroy pants kind of up over the belly button.

Stephen Katz [00:05:50]:

And I thought, we look just the opposite of these guys. Like, they look actually pretty cool, and we look like little schleppers. And then, of course, there was that catalyzing moment in February 9 when the Beatles were on the Ed Sullivan show. He eventually had rock groups that were sandwiched between plate spinners and puppets and opera singers and tap dancers. And then he would introduce some rock groups. So that was our opportunity to see bands. But this was the first big band, and in fact, there was 73 million viewers. So it became one of the biggest viewed event in television history.

Stephen Katz [00:06:34]:

The group's performance was so compelling, so full of youthful optimism that it kind of carved out the possibility of a new way to grow up. It was almost like we don't have to be factory laborers or join the army as boys anyway, or become salespeople or insurance brokers. We could be Beatles. We could be this other thing. And today, there's a huge industry that caters to that. There's fantasy music clubs, there's jam networks, there's joining cover bands. There's all kinds of homegrown activities in the basements and the garages across the land.

Sally Chivers [00:07:19]:

I'm realizing I only really knew beatlemania in retrospect, seeing coverage of women screaming after these long haired guys and thinking, wow, I guess that was radical then. But here, Stephen points out, this was another kind of role model, another way to grow up, another way to be a man. Now, of course, many of the boys with dreams to rock out end up working in factories, joining the army, becoming salespeople or insurance brokers or even professors. But wanting to be a rock star never gets old it turns out. Last episode, Stephen talked about a new era of retirement. And in this episode, we're going to talk in some ways about how that new form of retirement has spawned new rock star fantasies. As he points out, you can participate in fantasy rock bands.

Sally Chivers [00:08:18]:

I joked to Stephen about wives getting sick of their husbands hanging around the house after they retire and getting in their hair and telling them to go get a hobby. And then these boomer guys turning around and saying, okay, I'll get a hobby, but I'm going to infuse it with that youth and energy and counterculture hope I dreamed of when I watched the Ed Sullivan show in 1964. I'm finally going to be the freaking rock star I always should have been.

Stephen Katz [00:08:48]:

That's exactly the core of it, which is where identity and memory and fantasy and music and narrative and life course merge together. And maybe other generations have other merge points around other things. But this particular assemblage of personhood, I think, is unique. Not without some of the problems we discussed.

Sally Chivers [00:09:13]:

I'm just going to take a step back here and share with you what some of those problems are. In Stephen's own words,

Stephen Katz [00:09:19]:

the dreams and Fantasies of rock boomers are predicated on the heteronormative marginalization of women. Has huge, huge racial dimensions. Because of that, we also have kind of feminist rock. We have queering classic rock bands. We have gender transgressing boomer music, too. There's a great article by Norma Coates called Mom Rock, and I love that idea of mom rock, that you can be a mom and you can be a rocker too.

Sally Chivers [00:09:51]:

These gendered and exclusionary effects will be a topic of a future wrinkle radio episode. But I wanted to share Stephen's words here to make sure you knew that we were aware of it and he was aware of it. I partly wanted to separate him from the harm done, even in my own workplace, where all the guys were in a band together and then the women were expected to go to gigs and cheer them on alongside the students playing into this wannabe rock star fantasy. In some instances, the women were even assigned the role of serving food. We don't get to even pretend to be rock stars in our student's eyes I guess. For this episode, I wanted to dig into what was behind the fantasy behind the fantasy rock clubs that Stephen participated in and studied. Why do men want to be rock stars and what does that have to do with aging?

Stephen Katz [00:10:49]:

The wannabe ism that you're raising, I think is really fascinating. Why this wannabe ism? Why is it around the rock star? What is it that has perpetuated this endurance of an aspiration, of a trajectory, even if it never happens? It's always aspired to. That's what I find really fascinating.

Sally Chivers [00:11:19]:

These boomer aspirations extend beyond our own activities, onto our rock star idols pushing against the edges of the rockstar fantasy as they age before our very eyes. And at the same time, they're continually compelled to reenact their and our youthful dreams.

Stephen Katz [00:11:41]:

It's not just a masquerade of youthfulness, but it's kind of a tragic masquerade at this point. Witnessing this stuff like what is going on here? Mick Jagger, as you say, paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, they're all in their 80s, which would have been unimaginable in the Rolling Stones would still be going when they're 80. That would have been a ha ha moment. It's fascinating. And we also see, as you say, recent concerts being canceled due to health reasons. Bruce Springsteen canceled a bunch concerts because of a gastro problem. Paul Stanley of kiss had a bad flu and had to be in the hospital. A Toronto concert was canceled.

Stephen Katz [00:12:24]:

Steve Tyler of Aerosmith has serious throat problems. Madonna also had to cancel a few concerts. Stuff is catching up on them. Elton John is often out of breath. Keith Richards falls down on stage. Bob Dylan has no voice at all. Paul McCartney's lost his voice. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull can't sing anymore.

Stephen Katz [00:12:46]:

And after a while I'm going, what are these people doing? And these musicians have been asked this question. Their most typical answer is, what else do you expect us to do? We've done this all our life, and this is who we are, this is what we do. Some it's because of alimony payments and bankruptcies. Mick Fleetwood went broke a couple of times, so Fleetwood Mac had to keep going out. I don't know how much individual members of the Eagles owe.

Sally Chivers [00:13:14]:

As the effects of COVID catch up to people, younger stars are also starting to cancel concerts. So that is, of course, a factor. But for the rocker, Stephen talks about, it's not just their need to make money, it's that they're making money by playing a role for an audience who's growing old along with them.

Stephen Katz [00:13:36]:

Simon Biggs, a british gerontologist, uses the term the mature imagination. I think that covers this dilemma. I like that term, the mature imagination, to refer to how we maintain our inner integrity against the ageist and anti aging culture we live in, and how we look to fashion and sport and performance, and I would say music to keep our social belonging intact. There's this coercive asymmetry we all experience between our inner youthful self and our outer aging bodies. And that asymmetry needs to be accounted for. We have to negotiate that as we age. And I think when we hit our seventies and eighties and we're still inside in our twenties and thirtiess, which is what I think the boomer dilemma sort of is, then the mature imagination is really under strain to bring things up to reality. And so I think boomer musicians, famous and otherwise, old and young, perform this mature imagination to strengthen that continuity, to bring it in line, to make it possible to experience it.

Stephen Katz [00:14:47]:

Even though it is something of a fantasy when we watch these musicians on stage, in a way, rock performance invents the past as its past. It's a never ending version of the past in the present. It's a special kind of past that endures, that keeps going on. Even though I think it's strange that rock music boasts a reputation for change and revolution. It's really quite conservative, it's really quite backwards looking. Always kind of dependent on not just reinventing the present, but always reviving the past to be successful. Sometimes a classic rock musician records something unusual and creative, and the press jumps on them. Rolling Stone magazine.

Stephen Katz [00:15:37]:

Well, this isn't as good as their record three years ago, or what's Paul McCartney doing this for? And it's sort of like, hey, guys, we've got to keep you in line. We've got to keep you in that enduring past.

Sally Chivers [00:15:49]:

I love the questions this raises. How do we stay part of things even as we know our bodies are changing and the world is changing around us? What points of cultural and social contact can we still reach, or reach even better, now that we have time and money and a better sense of ourselves? We need these touchstones on the stage to stay the same so that we can continually connect to our youthful dreams. But Stephen and I also talked about how a continual attempted arrival of the past that never quite was is doomed to fall short. And I speculated with Stephen that there's something missing when you finally have the perfect cymbal and access to the recording studios you always dreamed about, instead of eking it out playing the upturn pails in your parents basement.

Stephen Katz [00:16:48]:

Yeah. No, you're so right. You're so right. That relates to some of the work I've done studying boomer rock fantasy clubs where bands are formed. And I participated in one. Yeah, it was a kind of auto ethnography project. Some clubs actually have famous musicians that work with you. Very expensive ones in Britain will have Roger Daltry, for example, or Eric Clapton.

Stephen Katz [00:17:13]:

You have to pay almost tens of thousands of dollars to be in a club with them. And you get to perform with them on stage. So it's a complete dream come true that you're in cream or the who or aerosmith or something like that. But the local clubs one I was involved in, I was interested to see that experience. You're talking about how being a rock and roller was actually produced spatially in rooms. How rehearsals and recording and stage performance were organized to create this memory, this generational boomer memory, to fulfill this fantastical dream of being on the Ed Sullivan show as a Beatle. It borders on non conformity and rebellion and finally doing something you want. And it also borders on just satire, on mirage.

Stephen Katz [00:18:09]:

When I go in with my band, sometimes to rehearsal facilities, there's five, six, seven rooms. And sometimes there's real musicians who rehearse. And we cross each other's path and look at each other, and it's like you guys are a mirage of what we actually are. Like we actually have to live on this. We have to make money and pay rent. And you guys, it's this fantastical hobby. And in fact, boomer fantasy bands can afford way more expensive equipment than actual bands. We can renovate our rec rooms, put in sound systems, have little jam sessions, buy vintage guitars that AC DC uses.

Stephen Katz [00:18:58]:

Or Eric Clapton once played on the Layla album in 1970 that costs thousands and thousands of dollars that real musicians actually can't afford. It's this ironic, almost satirical reversal of we're performing what they're trying to perform, but on the other hand, we can't play like them. They're real musicians.

Sally Chivers [00:19:22]:

I had to cut in here because I worried that I'd encourage Stephen to be too hard on himself. I see him as a real musician. Doesn't he?

Stephen Katz [00:19:32]:

Not really. No, I mean, I'm part time, I know how to play. It's not my source of income, first of all. And I did study music in university and learned it was great. It was really great. And I thought I might be a real musician, go into music, but I don't teach, I don't earn an income from it, I don't play regularly. If I stopped playing for a year, it wouldn't affect my life enormously. In other words, I probably just buy more cymbals and more drums, which I shouldn't do after a while.

Stephen Katz [00:20:08]:

I respect real musicians, of course. I mean, it's really, really hard work. And as you say, I'm starting to feel the arthritis in my hands. Being more tired after a gig, 3 hours of playing nonstop, usually little more backaches from schlepping around a big drum kit. Overall, yes. 71. Drumming, aching, physically worrying, mentally and emotionally wondering why I'm still doing this thing in my life when there's so many other things that could take up that time.

Sally Chivers [00:20:08]:

Even if you didn't know him before, by now you'll get the sense that Stephen is devilishly intelligent, devilishly funny, and also very down to earth. He's just described with some self deprecation his own participation in a rock fantasy band. And because he is down to earth and earnest, he knows that his dream of being a big rock star is also somewhat of a mirage. So there's more to it than the dream of making it big. There is more to participating in these rock bands even as it starts to hurt, it starts to cost more money, it starts to eat up time.

Stephen Katz [00:21:23]:

What I find interesting is the sociality of boomers being in bands together. How it gives them not just a personal belonging, but an interpersonal skill. It was a new opening up. I mean, as boys, anyway. In school, you could join sports teams, you could join bowling teams, you could join hobby clubs and photography clubs. But a rock band really skills you in relationality, especially amongst men. And I found that to be a really rewarding emotional vein in my life. I mean, when you're on a little, little stage with five other guys all sweating away and singing together and vulnerable and worried and trying to make each other sound good and arguing because a patch chord fell out or someone's volume is too high or low.

Stephen Katz [00:22:17]:

These take real emotional skills to kind of fix and negotiate. And in so many rehearsals I've had, half of it is talking and not playing and talking about ourselves and who's doing what to who and how we can help each other. And I think that's a really neglected but important, let's say, homosocial environment and skill. Men don't get a lot of opportunity to be that close. I mean, we're in locker rooms together and on basketball courts together, maybe in bars together or at funerals together, but on a regular basis, to be that close, to be that emotionally vulnerable and to be that intersupportive, I think, is a rare experience. And it's something I've really kind of appreciated and loved in my life going back to the age of twelve. That here was a new way not just to be a Beatle with the excitement and the fans, but to be a Beatle in terms of being in a group of males that grew up differently, that learned new things, that developed emotional skills.

Stephen Katz [00:23:26]:

And those skills, for me, have broadened into other relationships. I mean, they've been a real important training ground when there was no training ground socially for us. So being in a band in the 60s was also a chance to be socially grounded in a way that wasn't available by just being in a sports team, for example, or a locker room situation, or a bowling club. Those were pretty neat, but not as deep, not as lasting, and not as, in a way, vulnerable making.

Sally Chivers [00:23:59]:

Stephen plays now in a band called the Neckties. I'll provide links to YouTube videos of their performances in the show notes of this episode. I haven't been lucky enough to see them perform, but I have been with Stephen when they have a performance coming up. I thought his concern would be about his hands or his energy, but it was actually about being on call for other people in the band who may need to talk things through, need some kind of support, and just generally what I would call care.

Stephen Katz [00:24:29]:

I mean, we have a show this Saturday and already there's many, many emails and phone calls going back and forth. I wouldn't say as big as planning a wedding, a traditional wedding, but it's not that far off. We're really concerned about the minutiae, ot only of the music, but of each other, as you say, levels of confidence. Who can pull something off? Does someone need backup singing here? Should we not do that song because this happened last time? I mean, it's a lot of emotional fidgeting, but it's, I think, really meaningful. Even if we argue, even if there's conflict. Dealing with arguments and conflicts, again, especially for boys and men, we don't really have a blueprint for that. We just watch our parents, which sometimes are not the best models.

Stephen Katz [00:25:20]:

And other than that, I mean, maybe I'm wrong that girls grow up with more social opportunities that way, more communicative opportunities that way. And even now, there's a sense, I think, of girlhood as saving schools, saving sociality. I mean, so much pressure, it's almost gone the other direction. Girls cooperate. Girls share. Girls share toys, girls talk sooner. There's this kind of sense that the real educational moment is with girls. And boys kind of are like, they're competitive, they're aggressive, they don't talk, they're dumb.

Stephen Katz [00:25:57]:

And I think that's too bad. It's obviously kind of stereotyping, too, but boys grow up in that. And so a band gives us an opportunity to be different, to not be that way, which I really appreciated.

Sally Chivers [00:26:19]:

We've heard throughout this episode how being in a rock band can be beneficial in terms of social engagement, and then also how rock music offers a kind of blueprint for identity for the boomer generation when younger and when older. But I also wanted to leave you with these final words from Stephen about how you can't let that boomer identity take over the music.

Stephen Katz [00:26:44]:

In the end, the whole credo about being a boomer musician is to take the music more seriously than you take yourself. Because I think if you let that boomer identity intervene, which often happens, I want to be a wannabe wannabe, then the music suffers because you're not paying attention to the music, too. It's like, no, this is classic rock. This is what I'm play. This is the best music ever made. This is better than the eighties and the nineties. This is the great stuff. And you never get anywhere when your identity swarms over the music itself.

Stephen Katz [00:27:23]:

One thing I've learned is let that go. Play anything. If you want to play drums, play drums. Don't play boomer.

Sally Chivers [00:27:37]:

Thank you, Stephen, for your generosity and insight. In the early days of the COVID pandemic, I saw something online suggesting getting a mason jar and writing on a slip of paper the things you wished you could do, that you couldn't do. The idea was that at the end of all the isolation, you'd go back to this jar and you'd remember what you'd missed and you'd be able to go back to it. I started a jar, and I forgot about it. And when I discovered it recently, there was one slip of paper in it, and it said, go see Stephen's band. So, my friends and listeners, if you want to see a rock band, go see a rock band. This has been wrinkle radio. I'm your host, Sally Chivers.

Sally Chivers [00:28:31]:

Thank you for listening. Until next time, please tell your friends, tell your neighbors, tell your parents, tell your kids, tell the guys in your band. And remember, don't panic. It's just aging.

Music outro [00:28:48]:

I want to grow older. I want to grow wiser. I want to grow flowers in a house that's made of you. Just sit and watch the sunset. Get some wrinkles on my forehead. I want to be a fight. A house that's made of your.

Stacey Copeland [00:29:21]:

Listening to the Amplify podcast network.