Imagine Aging

PROJECT

Imagine Aging

Dr. Sally Chivers is Associate Director and leads the digital story strategy for the project.

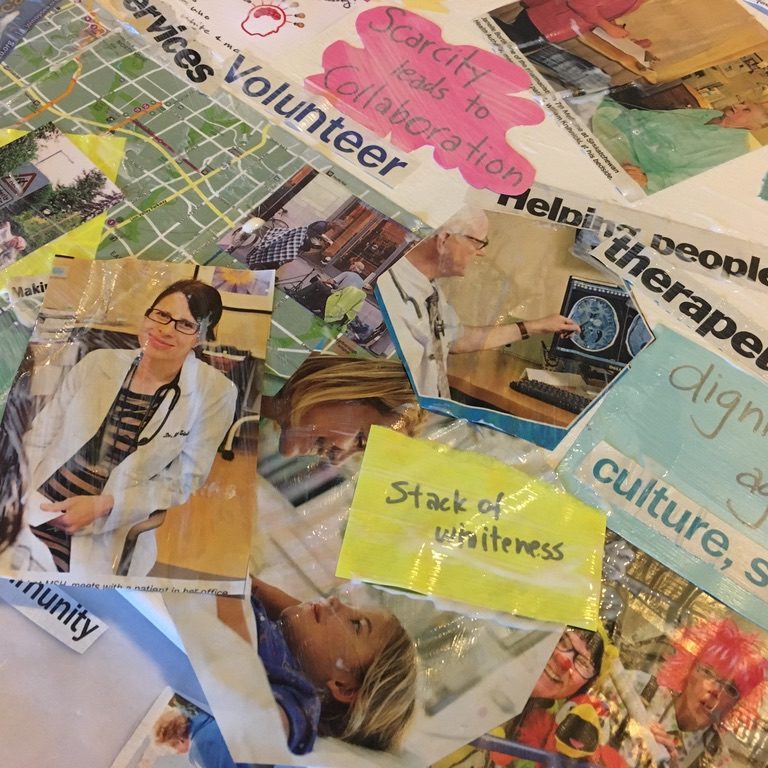

How do gender and culture matter in creating age-friendly communities?

With a focus on “communities within communities,” our research team seeks promising practices that ensure older adults not only maintain healthy active lives but also participate and create meaning in later life. We will study 12 cities in 6 countries (Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Denmark, Norway, and Taiwan) using ethnography, surveys, policy mapping, and arts-based methods. We consider a full spectrum of aging experience, especially of those people who are too often left out of programming and policy. We are learning about how change happens, and how our research can contribute to needed change.

Read the interview below to learn more about Dr. Chivers’s work with the team.

LISTEN TODAY!

Wrinkle Radio

Fight the forces that make aging worse for some people than for others. Join host Sally Chivers as we learn about aging through insightful stories, and celebrate along the way.

Imagine Aging, an interview with Sally Chivers

Q1 – What do we need to consider when we think about age-friendly cities

Age-friendly requires what I call ‘age integration.’ Our research focuses on older adults, as a group of people with particular needs, desires and contributions to make. But we also consider older people as part of a larger fabric that crosses generations. Many initiatives focus on intergenerational connections between old and young. That’s a great start, but the approach leaves out a wide swath of people from across ages and stages. In creating a truly Age-Friendly city, our project considers spaces that already congregate groups of people from across generations and across backgrounds, such as libraries, farmers markets, faith-based places, community choirs, and more. This makes sure we’re considering not only how older adults benefit from being around children, but also how the middle generations are part of age-friendly communities.

Q 2 – What do we need to pay attention to in terms of media, film and literary representations of aging?

Media, film and literature matter are the social and cultural pedagogy of our time. They teach us who we’re supposed to be and how we’re supposed to behave through appeals to the imagination. How we imagine aging affects what kinds of cities we can build and create and transform.

In mainstream media, the first thing we need to pay attention to is ageism, both blatant mockery or stereotypes and subtle insinuations that all older people need to look and act the same way, i.e. like younger people but with grey hair and maybe a couple of wrinkles. Grace and Frankie is a good example of a TV show that seems to value aging but also reduces it to ongoing productivity, activity, and beauty among the wealthy.

My research has found that literature has the potential to present a richer, more resonant view and perspective on aging than what we’re used to from mainstream media. A well-wrought novel can bring the reader in to share a mind space and an attitude on the world with an imagined older character. It can use figurative language, like metaphors and similes, to get out of the patterns that come with having human actors represent an older person. Of course, this is also possible with TV and especially with film, but the potential is richer within literature.

The problem with that, of course, is that people read less and less literature and are turning more and more to video and other forms of visual culture. So that’s why our project is committed to creating new multi-media representations.

Q3. Current discourse around aging and age-related health issues are centred around a cure vs. care narrative – Let’s either cure Aging or Let’s help care for aging. How can discourses on care and aging be reconsidered that promote broader understandings of aging?

Our research has long been part of the so-called relational turn where we emphasize that care is a relationship. When care is talked about as a relationship, it comes across discursively as one directional with examples such as a mother caring for her disabled child or a family caregiver figuring out strategies to help someone with dementia in their home.

I would love to see the discourse pick up what we have found in our qualitative research, which is that a family caregiver might take care of someone with dementia at home and the person with dementia is still contributing meaning, life, structure, and even joy day-to-day. This is why, as I said in the previous answer, deliberately artistic and imaginative visions of aging can help us rethink and broaden past a cure vs care approach in which care then becomes either a burden or an act of charity. If you’re looking for an example, try watching the movie Mango Dreams, and then we can talk about how it intervenes in dominant ideas about care as one-directional.

Q4. How can we reconcile tensions between an ageist and an age-friendly approach to aging in society?

The Age-Friendly movement developed in response to widespread ageism. But it was slowed right out of the gate by its attachment to prescriptive ideas of Active Aging and Healthy Aging that rest on ageist thinking.

Cultural gerontologists and critical gerontologists have pushed back against active aging for years because of the ways that it forwards neoliberal goals and because of the ways it promotes a form of ageism. If we want a genuinely age inclusive world, we have to get away from valorizing active aging in a way that ignores a range of activities and ways of being in late life. Frode Jacobsen, a member of our team, has published a phenomenal article that goes through the use of these kinds of terms in Norwegian white papers. Every time I read it, I find something new. That work offers a launch point from which we can really notice the harm that the idea of active aging can do, as well as to come up with other ways to talk about aging constructively.

Q5. Why is it important to consider gender and racialization when we consider aging and ageism?

To adapt a popular saying, our age studies will be intersectional, or it will be bullshit.

I don’t see how we can talk about ageism without talking about gender and racialization. And I would add ableism. Aging is a gendered process, a social process and a racialized process.

If you hear the phrase “residents in a nursing home,” who do you picture? What do they look like? How old are they? How do they move around? What is their gender? I think if you take a moment and do that, you’ll notice how aging and our own internalized ageism is racialized. Who is believed to deserve good care is a highly racialized category, and so is who does the underpaid and undervalued work of care.

Finally, it’s essential that age doesn’t replace gender and race as an identity category. We don’t want people becoming old instead of being a woman, for example. That’s something Susan Sontag wrote about as the double bind of aging for women. Beyond that, in invoking intersectionality, we have to go beyond adding identity descriptors to account for lived experiences and social structures. That’s why we arrange our research team in theme groups that investigate lived experiences, organization, and constructions of aging as they relate to power and identity.